I am going to share with you excerpts from a research paper I wrote in 2018 about Tesla and electrical vehicles (EVs), which I have turned into a small book for reader convenience (it is available for free, here). I want to share these essays with you today because we are at a pivotal moment for traditional carmakers, and these essays, which I have not updated, present an important thinking framework about the industry.

It is easier to convince shareholders and the board of directors to invest money into new factories when the demand for EVs is growing, even if you are losing money per vehicle. At least there is hope that once you get to scale and perfect new technology, the losses will turn into profits.

However, when the demand for electrical vehicles stutters and your inventory of EVs starts piling up – which is exactly what is happening right now – investing in EVs becomes very difficult (I wrote about it here). Retreating to what you know, what has worked for almost a century, what doesn’t generate huge losses with every vehicle sold, and what your current workforce is trained for, and comfortable producing, seems like a natural decision. The decisions traditional carmakers will make over the next year or two will be very important for what their future looks like a decade or two from now.

“What you really should have done in 1905 or so, when you saw what was going to happen with the auto is you should have gone short horses. There were 20 million horses in 1900 and there’s about 4 million now. So, it’s easy to figure out the losers; the loser is the horse. The winner was the auto overall. But 2000 companies (carmakers) just about failed.”

– Warren Buffett, speaking to University of Georgia students in 2001

Can traditional automobile companies successfully transition to making EVs?

Today EV sales account for a tiny rounding error of total global car sales. Let’s mentally transport ourselves to the late 1800s, when the streets were still busy with horse-drawn carriages and the occasional passing automobile scared a horse or two.

If you cannot relate to a century-old analogy, let’s go back to something that happened just a bit more than a decade ago. In June 2008, when the iPhone 3G was introduced, Nokia was still the largest phone maker in the world. What we did not know at the time was that Nokia was the largest dumb phone maker and that Apple was about to become the largest smartphone maker – a small but crucially important nuance. What we did know at that time was that smartphones were the future.

In theory, nobody knows more about making cars than the traditional ICE carmakers – the General Motors of the world – and thus EVs made by these companies should be the ones busying our streets a decade from now. A natural continuity from what we already know may be the easiest cognitive model for us to process, but it is not always the most accurate one.

In 2004, Nokia missed the flip phone boom and lost market share to Motorola, which came out with the slick Razr flip phone. Nokia had a few quarters of disappointing sales, the stock declined, and we bought it. Then Nokia came out with its own flip phone and the status quo was restored: The company was again king of the dumb (actually, let’s be politically correct – mentally disadvantaged) phone castle. The flip phone was a technological change, but it was still in Nokia’s domain of core competency. The stock ran up and became fully valued; we made money and sold it. We patted ourselves on the back.

Now, the mistake many investors made, including yours truly, was not seeing that although the iPhone was still called a phone, it was not really a phone but rather a portable computer that, in addition to doing a lot of other smart things, also made phone calls (which the first iPhones were not really good at, but the people who owned them didn’t really care). It was not Apple that dethroned Nokia, not at all. Nokia did it to itself. Nokia should have looked at the iPhone and blown Apple a huge air kiss, thanking it for showing the future of “phone,” and then gone on to develop its own smartphone.

I made the mistake of applying my 2004 mental model to our Nokia purchase in 2008. With the introduction of the iPhone, Apple took a mentally disadvantaged phone and pushed it into a very different domain with a very different ecosystem.

Assets turn into liabilities

Nokia was a very efficient designer and manufacturer of phones that had very little software and limited functionality. In 2008, the company employed thousands of engineers who knew a lot about wireless signals, plastics, moldings, coatings, and so forth. But collectively they knew little about CPUs, software, and user interfaces. Nokia tried to respond to the iPhone the only way it knew how – by taking its Symbian operating system designed for low-IQ phones and trying to remold it into a smartphone operating system. That attempt failed miserably. We realized what was happening later than we should have and gave up a good chunk of our 2004 Nokia gains.

I never thought I’d say this, but knowledge is not always an asset. When you are in the middle of a transition from one domain to another, your knowledge of the past domain may cloud your vision. You’ll be seeing through the lenses you’re used to wearing.

When the first cars were made, they didn’t have steering wheels, they had tillers, because they were made by a horse carriage manufacturer. Though it was possible to transition from making horse carriages to making cars, most companies did not; they were stuck in the old “buggy” domain and did not switch to the new “auto” domain.

It is difficult to kill your cash cow

Clayton Christensen discussed this concept in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma. When your core business is minting money, it is difficult to create another business that may be future-proof but will undermine your core business, especially if the threat is nascent at the time and seems far away. These threats are usually nascent and far away.

When Amazon was practicing e-commerce on books, everyone believed Barnes & Noble would be able to suffocate the tiny company because B&N sold more books in a day than 1997 Amazon sold in months. However, snuffing out Amazon would require Barnes & Noble to lower online and possibly in-store prices, which would hurt its very profitable store business. Well, we all know how that story ended.

The transition from ICE cars to EVs is not just a technological shift within a domain. It is not like the transition from two-wheel-drive sedans to four-wheel-drive SUVs; it is a radical shift into a new domain. I laid out this very extensive domain-shift framework to show that the success of ICE manufacturers in this new domain is anything but guaranteed. Let me expand this framework even further.

ICE cars are low-IQ phones, and Tesla’s Model 3 is an iPhone 3G. Cars last about 12 years and phones two to three, so this transition will happen in slow motion.

As I discussed, during the transition from one domain to another, many of the assets and much of the knowledge from the old domain become liabilities in the new one.

Tesla created its cars by entirely breaking out of the domain of existing auto manufacturers. Although this is true for the Model S and the Tesla cars that followed, it was not the case for Tesla’s first car, the Roadster. When Tesla first attempted to make an electric car, it was constrained by resources. It wanted to experiment with battery technology and electric engines and did not want to design a complete car. So, Tesla adapted the body and powertrain of the Lotus Elise, a sporty gasoline car. Later Elon Musk confessed that had been a mistake – he compared it to keeping the outside walls of a house but gutting and rebuilding the inside, including the foundation. You might as well build a new house.

Because Tesla created the EV industry, it had the advantage of acting from first principles. It could start thinking with a blank piece of paper, not redrawing what already existed. In an interview, Musk said, “I tend to approach things from a physics framework … physics teaches you to reason from first principles rather than by analogy.”

Warren Buffett’s version of first principles is “What would Martians do if they landed on our planet?” Not because of Martians’ enormous IQs but because they would be new to our planet and could see with clarity things we often don’t because we’ve been here so long.

The first-principles approach allowed Tesla to build EVs that are free of the limitations of gasoline-car thinking. No gears, a skateboard chassis, two engines, a frunk, a credit card key, a mobile app that works as a key and controls the car, and no start button, among others – Tesla applied first-principles thinking to how its cars would be sold. The Model 3 feels like it was designed starting from a completely blank piece of paper and this thinking extended beyond the car and spilled over to selling and servicing the car.

Today’s ICE auto manufacturers are basically wholesalers of their cars to auto dealers that are their franchisees. This business model is a Great Depression relic that went basically unchallenged until Tesla came along. The model worked well for automakers and dealers for almost a century, though the experience most consumers had did not fit the definition of well.

Tesla decided that the traditional business model was not appropriate for the new EV domain. Instead, it borrowed a model from Apple, which controls the full customer experience, from buying a phone to servicing it to upgrading to a new one. Also, electric vehicles have fewer parts than ICEs and thus should break a lot less (at least in theory – time will tell), so the traditional dealer model that relies on service revenue doesn’t work well for EVs.

This journey of opening its own stores was anything but easy for Tesla. It had to fight opposition by ICE carmakers and local dealers in every state, just as Uber had to fight taxi monopolies.

My purchase of a $51,000 Tesla (in 2018) was as easy as my purchase of a $900 iPhone. I test-drove it. A few days later, I called the Tesla store and told the salesperson that I wanted to buy a car. My information was already in the system; I had to provide it when I placed my deposit in 2015, and I had to confirm it when I scheduled a test drive. I just told the salesperson the configuration I wanted and placed a fully refundable credit card deposit. (I was traveling, but I could have done all this from Tesla’s iPhone app or website.) A few days later, I got an email confirming my Model 3 delivery date and asking me to schedule a time to pick up the car. On June 29 at 9:30 a.m., I appeared for my car; by 9:40 I was driving back home. It was that simple.

Tesla changed how a car is serviced, too. A few weeks after I bought the car, its speakerphone stopped working – people could not hear me. I went into the Tesla iPhone app and requested service. I was given a choice between bringing my car to the Tesla service center or having a service technician come out to me. I chose the latter. Two days later, the technician showed up at my office. I gave him my car key and went back to doing research. An hour later, my car was fixed. Tesla’s technician had simply restarted my computer. In hindsight, I could have called Tesla and my speakerphone issue could have been fixed remotely.

Now compare these buying and servicing experiences with buying and servicing an ICE car.

It is difficult for ICE companies to adapt first-principles thinking, as it requires them to unlearn what made them successful in the old domain. They are going to have to retool their factories (the smallest challenge of all). They will need to go through a significant and painful change of their workforce. Their current employees have a very different skill set and look at the world through petrochemical lenses (which explains why GM’s first foray into electric was the Volt, an electric car with a gasoline engine attached).

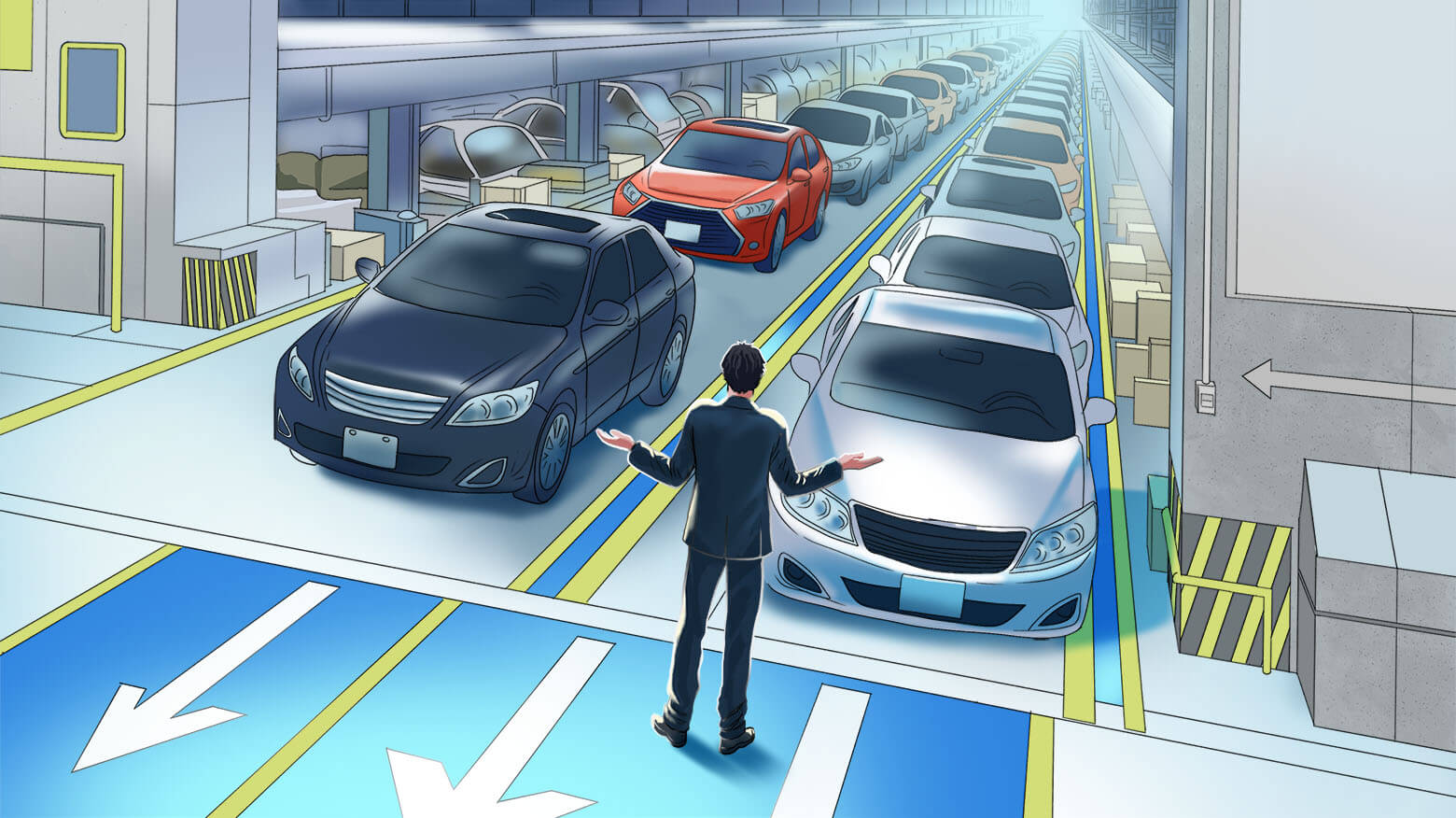

Auto dealers, which are an asset to car companies today, will turn into liabilities tomorrow, as Tesla’s direct distribution and service model should provide a cost advantage once it gets to scale. Tesla’s model is more customer-friendly and efficient, allowing the company to capture the profit that ICE carmakers have to share with their dealers. Because a good chunk of Tesla’s cars are built to order, the company doesn’t need massive inventory sitting on giant parking lots. Also, ICE manufacturers may not be able to replicate Tesla’s direct-sales business model because they are stuck with the franchise agreements they signed with their dealers.

It won’t be easy for ICE carmakers to adapt first-principles thinking to their EVs, but they may not need to: They can copy Tesla. The existing players are not automatically doomed. William Durant, who turned struggling Buick into General Motors, originally made his millions on horse-drawn carriages.

Understanding the enormity of the needed investment, carmakers are creating alliances. Ford and Volkswagen are working together on artificial intelligence (AI) and skateboard chassis for EVs. Historically, such alliances in the auto industry have had mixed success.

Traditional car companies have a lot of things going for them. Their strengths are in the designing, assembling, and marketing of cars. They use hundreds of suppliers to make the parts that go into their cars. They can do the same thing when it comes to EVs. They can outsource the battery to LG Chem or Samsung. They can outsource software design to the likes of Cognizant and DXC. They can use Waymo’s self-driving software and Nvidia’s self-driving hardware. The traditional automakers are in their best financial shape in decades and thus have capital to finance the EV adventure. They can afford to make an enormous investment in EVs and take the losses that come with them. But will they? I don’t know.

To some degree, their job is more difficult than Tesla’s. They have to keep innovating as they make horse carriages – sorry, I mean ICE cars – because ICE cars are what pays their bills. At the same time, they have to focus on the future and invest enormous amounts of time and capital building EVs.

When Hernán Cortés invaded Mexico, legend has it, he ordered his army to burn all its boats. He wanted his soldiers to fight as if there was no way back. This is how Tesla is approaching EVs – no boats. ICE companies today seem like tourists in EV-land, with comfortable (ICE) cruise ships waiting for them offshore.